What Are The Five Main Parts Of A Tree Trunk Called?

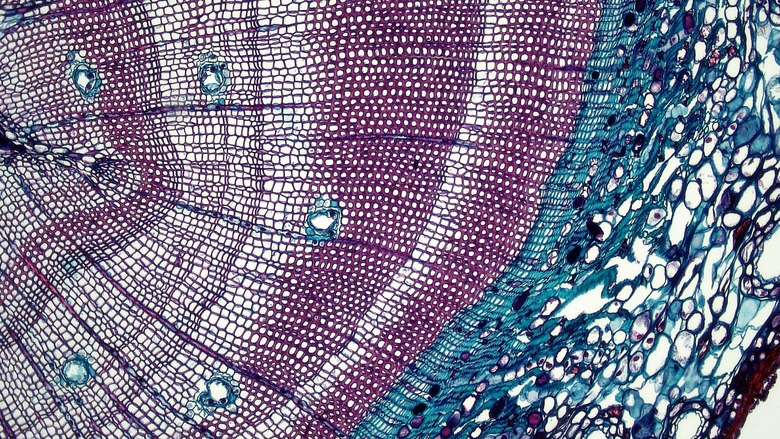

Also called a bole, the trunk of a tree comprises 60 percent of a tree's mass, so it's remarkable that this largest part of a tree is mostly dead tissue. Only a thin band around the outside of a tree trunk contains living tissue, and this living ring typically is less than one-half inch wide in large trees (thinner in smaller specimens).

But even the nonliving parts of trees perform vital functions, such as protection and support. There are five main parts of a trunk, each of which has a specialized role to play in the overall growth and health of trees.

**The five main parts of a tree trunk are:**

- Outer Bark

- Inner Bark/Phloem

- Cambium

- Sapwood/Xylem

- Heartwood

Outer Bark

Varying widely in appearance depending on different tree species, the outer bark is the part of a trunk that first meets the eye.

Some trees have smooth bark, such as American beech (Fagus grandifolia, USDA zones 3 to 9). Many species have deeply textural bark, such as pitch pine (Pinus rigida, zones 4 to 7). And some trees are prized for the landscape interest of their exfoliating bark, such as paper birch (Betula papyrifera, zones 2 to 7).

Even though this bark is dead tissue, it performs an invaluable service to trees by protecting them from potential hazards such as adverse weather, insect pests and injury. The outer bark can also protect a tree by retaining moisture during periods of drought.

Inner Bark/Phloem

Directly underneath the outer bark is the inner bark, also called the phloem. This vital part of a tree trunk is responsible for nutrient transport.

As a product of photosynthesis that occurs primarily in the leaves, sugar travels down the phloem from the canopy to the roots, where it's stored for future nutrient needs, or moves to other parts of a tree for immediate nourishment. The phloem also transports amino acids, hormones and vitamins.

Cambium

The cambium layer is made up of living cells that grow from the inside of a tree outward instead of up and down a tree trunk. As this layer grows, it results in new bark on the outside and new wood on the inside.

When leaf buds produce auxins, which are plant hormones, the phloem transports them to the cambium where they stimulate this new growth. As the new growth is dying, its functions weaken until eventually it dies and provides only support for the tree.

Sapwood/Xylem

The sapwood inside a trunk is the largest band inside a tree. It is the pipeline through which water and dissolved minerals move from the roots upward throughout a tree all the way to its crown.

As the sapwood pulls water from the soil, it also filters out impurities to protect the health of a tree. This natural process has been studied by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The scientists made water filters from sapwood, which successfully filtered out pathogenic bacteria from contaminated groundwater as well as tap water. Although the sapwood they used was from tree branches, the same process occurs in the sapwood of trunks.

Tip

The sapwood supports a hydraulic process that allows even towering trees that are hundreds of feet tall to stay hydrated.

Heartwood

Of all the parts of the tree trunk, the heartwood is the primary support for the tree that's located at the center of the trunk. Although the heartwood is dead xylem tissue, curiously it will not decay or lose structural integrity while the sapwood and bark are in place.

It's easily identifiable when logs are cut because it generally has a darker color than the surrounding sapwood.

References

- University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension: An Introduction to Wood Anatomy Characteristics Common to Softwoods and Hardwoods

- Virginia Tech: A Tree and Its Trunk

- University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Extension: Basic Components of Tree Biology

- Michigan Forests Forever Teachers Guide: Tree Physiology

- Texas A&M Forest Service: How Trees Grow

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT Engineers Make Filters From Tree Branches to Purify Drinking Water